By Emily N. Giddings, MSN, RN, CNE, CCRN

Keep in mind that no number of test-taking strategies can replace adequate preparation with content review and practice with critical thinking and clinical reasoning. That said, helping students develop strategic methods for approaching questions may reduce their anxiety and enable them to practice more effectively. We aim to discuss evidence-based approaches that can empower your students to test with confidence.

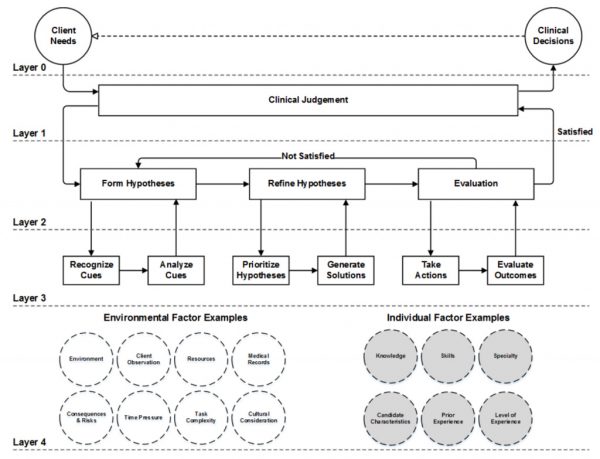

The Clinical Judgment Measurement Model as a Practice Framework

As nursing practice becomes more complex, the NCLEX® has as well, with first-time pass rates of US-educated graduates steadily declining for three consecutive years now (NCSBN, 2018, 2019a, 2020). While nursing’s conventional test strategies (ie, Maslow’s, “assess first”) can be useful, the practice environment and its requisite licensing exam are now asking much more of graduates. Scanning for bolded words and prioritizing the airway are not novel test-taking strategies. In the face of the heightened NCLEX challenges and upcoming Next Generation transition, we must re-examine how we coach our students to approach questions.

Fortunately, the NCSBN’s Clinical Judgment Measurement Model (CJMM) has operationalized a simple cognitive model for clinical judgment (Dickison et al., 2016):

- Form hypotheses

- Refine hypotheses

- Evaluate

Note. Testing strategies adapted from layer two. Copyright NSCBN®, 2019b.

Although its intended use is as a measurement model, the NCSBN also encourages educators to integrate the CJMM as an educational framework (Dickison et al., 2019). We believe your students will find this application of the CJMM useful in breaking down the thought process embedded in clinical judgment. You will see that this model incorporates several familiar bedrocks of testing strategy. However, the streamlined, three-step process will enable your students to keep these salient steps in mind without becoming overwhelmed. Practicing this approach now will also benefit students who will be tested under the Next Generation NCLEX beginning in 2023, which walks students through these same cognitive steps in an unfolding manner.

FREE: Form hypotheses, Refine them, Evaluate outcomes, Explanation review.

1. Form hypotheses

- Read the stem carefully, before ever looking at the options, and envision the clinical scenario. Picture each client scenario using every descriptor provided.

- At face value, a client with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who has “an oxygen saturation of 90% while eating breakfast,” may sound scary and set off your students’ alarm bells for issues of airway or breathing. However, visualizing this scenario helps reproduce the clinical picture the item writers intended to convey. Drawing on all available cues enables your students to better analyze context and enhances information retrieval (Lieberman, 2020).

- Now, hypothesize: a) what is currently happening with the client(s), b) what needs to happen, and c) in what time frame (referred to in the CJMM as time pressure). Is the stem asking what you would do “next,” “first,” or as a “priority”? These terms mean different things. Once the student decides what needs to happen with the client, they are prepared to read the options.

2. Refine hypotheses

- Review the options, and eliminate any known incorrect answers. If something in an option registers as a known safety risk, students should immediately eliminate this hypothesis. This allows students to focus only on the remaining options.

- Consider any additional information presented within options. Maybe the most important intervention a student envisioned for a client with wound dehiscence and bleeding is to be taken to the operating room emergently. However, the student now sees that only one option includes an action that would lead to surgical intervention: paging the healthcare provider. The student refers to the time frame defined in the prior step, which asked what to do next. This decreases the strength of a distractor that would delay care.

3. Evaluate outcomes

- Consider how each remaining option would play out. If a student chooses an option, what will happen? In the case of our hemorrhaging client:

- If the student chooses to page the healthcare provider, what happens next? Will they stand there and watch the client bleed out while waiting for the healthcare provider to arrive?

- Maybe the item includes an option to “take the client’s blood pressure.” This incorrect option is attractive to students according to the “assess first” prioritization principle. However, evaluating this option’s outcome should reduce its attractiveness as a distractor: is the student to stand there waiting for the blood pressure cuff to cycle while the client continues to bleed? Additionally, will taking the client’s blood pressure change anything? No, the client likely requires emergent surgery regardless of what the blood pressure is.

- Finally, what about the option to “place pressure on the site and call for help”?

- This step is crucial to navigate students away from strong distractors or second-guess an option that may not follow the ABC, Maslow’s, or “assess first” conventions.

- Select the correct answer.

4. Explanation review (if answering questions in a practice test)

- Maybe most importantly, students should review the explanation, regardless of whether they answered the question correctly or incorrectly. As educators, we all know the merits of problem-based learning and its utility as an active learning method. Students who just completed this cognitive process are now primed and ready to receive new information that will translate to future scenarios and test questions they encounter (Sayyah et al., 2017).

- This is the best time to expose students to this content and is much more engaging than learning the same content (i.e., hemorrhage management) as delivered passively in a lecture. This has taken them from the knowledge level (“clients with hemorrhage require emergent surgery”) to the application level (“clients with hemorrhage need the bleeding stopped, and before they can go to surgery, I should do whatever I can to stop the bleed now, such as hold pressure or apply a tourniquet.”)

- Explanations should break down precisely why each option is correct or incorrect, and incorrect options should contain strong teaching points. This enables them to translate this new understanding to as many other questions as possible. In our example scenario, students now have not only learned to apply hemorrhage management, but also have a better sense of when something is too urgent to delay care, and when assessing first may not be useful. This one practice question will aid them on numerous others.

Serendipitously and unintentionally, this approach can be remembered using the mnemonic FREE: Form hypotheses, Refine hypotheses, Evaluate outcomes, and Explanation review. If this thought process seems tedious at first, keep in mind that students will refine this approach over thousands of test question practice sessions. They may need to keep a checklist handy when they first begin to practice, but after several hundred questions completed over many weeks, this process should become second-nature. We want our students to be so comfortable in their specific, deliberate practice that once they pass, they will report that “the NCLEX felt like just another practice test.”

The earlier students begin practicing in this way, the longer they will be able to space their practice sessions over time. This spacing effect enhances student performance much more than if the same thousand questions were reviewed over a shorter period of weeks or months (Kim et al., 2019). This is why UWorld suggests introducing question bank review as early as students’ first semester.

Check out our article on How to Practice Test Questions to see how this model fits into the bigger picture. We are excited to provide you with this framework and look forward to hearing how this helps your students. Please contact us with any thoughts, comments, or success stories.

References

Dickison, P., Haerling, K. A., & Lasater, K. (2019). Integrating the National Council of State Boards of Nursing clinical judgment model into nursing educational frameworks. Journal of Nursing Education, 58(2), 72–78. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20190122-03

Dickison, P., Luo, X., Kim, D., Woo, A., Muntean, W., & Bergstrom, B. (2016). Assessing higher-order cognitive constructs by using an information-processing framework. Journal of Applied Testing Technology, 17(1), 1–19. http://www.jattjournal.com/index.php/atp/article/view/89187

Kim, A. S. N., Wong-Kee-You, A. M. B., Wiseheart, M., & Rosenbaum, R. S. (2019). The spacing effect stands up to big data. Behavior Research Methods, 51, 1485–1497. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-018-1184-7

Lieberman, D. A. (2020). Learning and memory (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108553179

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2018). Number of candidates taking NCLEX examination and percent passing, by type of candidate [Data set]. NCSBN. https://www.ncsbn.org/Table_of_Pass_Rates_2018.pdf

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2019a). Number of candidates taking NCLEX examination and percent passing, by type of candidate [Data set]. NCSBN. https://www.ncsbn.org/Table_of_Pass_Rates_2019_Q4.pdf

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2019b). The NCSBN Clinical Judgment Model. NCSBN. https://www.ncsbn.org/NGN_Spring19_Eng_04_Final.pdf

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2020). Number of candidates taking NCLEX examination and percent passing, by type of candidate (Q3) [Data set]. NCSBN. https://www.ncsbn.org/Table_of_Pass_Rates_2020_Q3.pdf

Sayyah, M., Shirbandi, K., Saki-Malehi, A., & Rahim, F. (2017). Use of a problem-based learning teaching model for undergraduate medical and nursing education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 8, 691–700. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S143694